Gran Selezione can be, should be and deserves to be a mark of excellence and a brand recognized across the globe for wines of utmost quality and tradition.

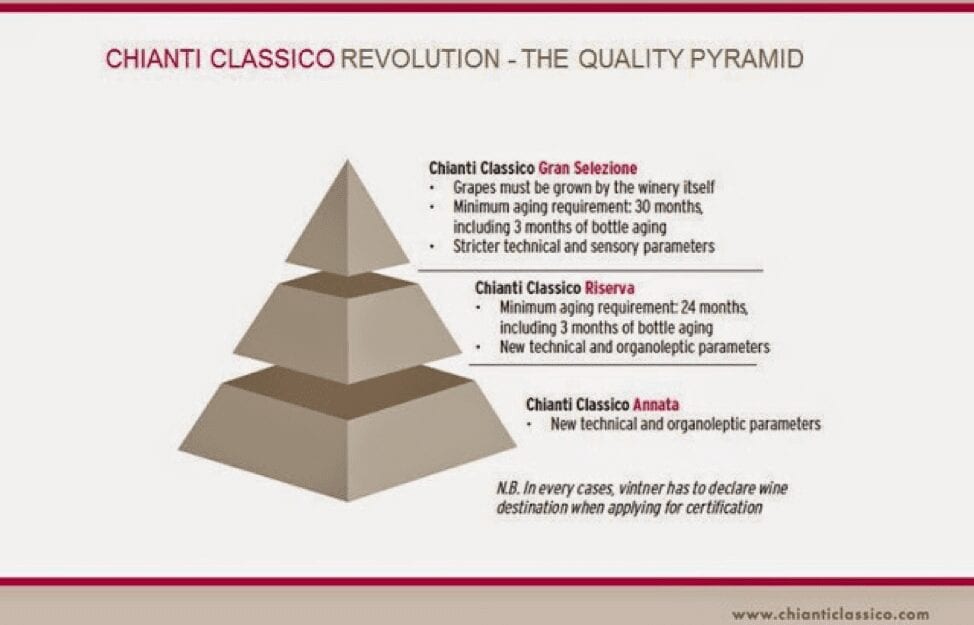

In the Spring of 2016, the Chianti Classico Consorzio debuted and showcased their greatest expression of Chianti Classico; Gran Selezione. The tasting event began with a panel discussion headed by then Consorzio President Sergio Zingarelli, who addressed the new designation and explained how it differed from the previous pinnacle, Chianti Classico Riserva. It seemed simple enough. In order for producers to label their wines using the new Gran Selezione designation, the wines must be produced solely from estate grown grapes, include at least 80% Sangiovese and be aged 6 months longer than Riservas prior to release.

However, once the tasting began, various questions began gently simmering to the surface of the conversation throughout the room.

What is Gran Selezione supposed to represent?

How can you possibly compare these wines to each other?

Will this designation confuse the consumer?

Why are some of these wines so expensive?

Doesn’t this designation relegate Chianti Classico Riserva to inferior status?

If this designation is meant to be prestigious, why are so many producers against it?

Here we are, almost three full years removed from that tasting and we’re nowhere close to being able to answer these questions. Many pundits and critics, myself included, have urged producers and the Consorzio to move toward producing Gran Selezione with 100% Sangiovese. Producers straddle both sides of the fence; many agree with the idea, but many do not.

The former believe that Gran Selezione should exalt Tuscany’s native Sangiovese grape and finally be able to show the greatness of mono-varietal wines similar to that of their Southern cousin, Brunello. They argue, after all, that it was inferior red and white grapes, which were mandated in Chianti Classico during the 1970s, that energized the movement spearheaded by Piero Antinori toward creating premium IGT wines in the first place. Therefore, it’s only logical that pure Sangiovese should be the backbone of Gran Selezione.

Conversely, the latter believe that the heritage of Chianti Classico was always based on a blended wine and they staunchly support native grapes such as Canaiolo, Colorino and Malvasia Nera. Consequently, many favor continuing that tradition and some producers even bristle at the inclusion of any non-native varietals.

So what’s the right answer? Does it matter? Should it matter?

In order for Gran Selezione to provide an exceptional experience and one that consumers can understand and rely upon for consistency, Gran Selezione wines must be at least 90% Sangiovese, thereby minimizing the impact of the remaining grapes comprising the blend. While there is an argument to support 100% Sangiovese wines, one can understand and appreciate the tradition that blending represents. Encouraging these percentages should lead to a recognizable wine and a branded product that represents a consistent experience for the consumer who can then buy Gran Selezione with confidence. Current law requires Gran Selezione to be at least 80% Sangiovese. The understanding is there. An additional 10% mandate should not be difficult to implement.

So what’s the big issue surrounding the blending? Wouldn’t the devil’s advocate response to a call for blending consistency be a risk of boring homogenous wines?

Maybe. However, the confusion and potential damage to the brand is a much greater risk than wines that seem homogeneous. Remember, I advocate blending 10% of other grapes along with Sangiovese and while that won’t dominate the Sangiovese, it can create intriguing differences that reduce the risk of blandness. Consider this cautionary true anecdote.

A prominent producer’s Gran Selezione is comprised of 6 different grape varietals including Sangiovese, Abrusco, Pugnitello, Malvasia Nera, Ciliegiolo, and Mazzese. And no, I’m not making up those names. Imagine that a consumer buys this wine and really enjoys it, and then on a subsequent trip to their wine shop, buys another “Gran Selezione” from a different producer. Except the second bottle they buy is 80% Sangiovese and 20% Syrah. If they’re displeased with that wine, what might they think about the “Gran Selezione” designation? Or worse yet, what if the scenario were reversed? What if their first experience with Gran Selezione is a wine that’s 80% Sangiovese and 20% Cabernet or Merlot? A wine of that blend is likely to be lush and fruit forward compared to the six grape blend described above. Who does that benefit? The consumer? The Consorzio? Certainly not the Producer in question. This issue remains widespread.

At the Gran Selezione event I mentioned at the outset, the wines poured were produced from the following grapes in some combination: Sangiovese, Canaiolo, Colorino, Malvasia Nera, Mammolo, Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Franc, Petit Verdot, Merlot, Syrah and Alicante. That’s 11 different grapes! Factor in the obscure varietals mentioned in the story above and the number jumps to 15.

How can you respect, portray and exalt the tradition and terroir of a region as illustrious as Chianti Classico when you have this much variability in wines that bear the same name: “Gran Selezione”?

Blending is only the beginning. Since we’re not starting from a uniform place, imagine the exponential variants that can occur when you layer the following factors onto the finished wines: barrique vs. botte aging, cement vs. stainless steel vinification, length of aging, soil types, vineyard elevation and vineyard exposition to say nothing of the general differences in geography between the extremes of San Casciano in Val di Pesa and Castelnuovo Berardenga. (See the map below)

Beginning with a more uniform starting point will allow the differences in terroir and winemaking styles to become amplified. This is part of the reason Brunello is so lovely. There is a stark difference between a Brunello from a high elevation vineyard located north of Montalcino and one created from lower lying vineyards closer to San Angelo in Colle. Good? Bad? That depends on your palate. But the differences are notable.

In the absence of compelling direction from the Consorzio, the fate of Gran Selezione lies firmly in the hands of the producers. Their preferences for style, aging and blending will continue to drive what’s in the bottle and in turn shape what Gran Selezione is. That is the reality though I’m not sure it was the Consorzio’s intent.

The other issue plaguing the designation is pricing.

Price is a twofold issue, but let’s start with the cost of an average Gran Selezione. Generally speaking, most examples cost about $50. However, many are between $100-$150 per bottle. I’m left shaking my head here. As an educated consumer, are you really going to spend that kind of money for a single bottle of Gran Selezione when you could buy 2-3 bottles of wonderful Brunello for the same cost? Or 3-5 bottles of excellent Chianti Classico Riserva? And that brings us to the second issue regarding pricing.

Most interested parties agree that Gran Selezione should represent the pinnacle of wine from Chianti Classico. If that’s true, doesn’t that hurt producers whose best wine is a Chianti Classico Riserva? How you say?

Imagine a small producer who crafts an exceptional Riserva as his top wine. Although he could label his wine Gran Selezione but for the additional aging requirements, he’s unable to do so. The scale of his business, the limited space to store wine in his cellar and the delayed cash flow caused by holding the wine an extra 6 months will adversely impact his business. It’s not practical or economical for him to do so.

For many small producers, these are real and valid concerns. Some feel as though they’ve had their brand left behind by the Gran Selezione designation and they feel slighted by the Consorzio. Furthermore, since it’s easier for large producers to meet the demands of aging because they are not uncomfortably pinched by delaying their revenue stream, some producers feel as though the designation has created a rift between large and small producers.

To illustrate further, imagine a small producer whose flagship wine is a Chianti Classico Riserva that retails for $50. Imagine it sitting on a merchant’s shelf next to a Gran Selezione that is also priced at $50. Since Gran Selezione is supposed to be “the best” wine from Chianti Classico, which wine will the average consumer choose? To take this pricing notion further, isn’t the “price ceiling” for Chianti Classico Riserva now artificially fixed by the “price floor” of Gran Selezione? These are not artificial or abstract hurdles and need to be addressed by the Consorzio.

So where should the Consorzio head?

The Consorzio must be the driving inertia that propels Gran Selezione to the consumer recognized greatness it can achieve. It alone can lead this initiative while protecting the interest of their smaller producer members.

Gran Selezione can be, should be and deserves to be a mark of excellence and a brand recognized across the globe for wines of utmost quality and tradition. To get there, the Consorzio must work to limit the variables that can water down the brand and lead to consumer confusion. The creation of the designation was a significant first step. Now is the time to perfect its natural evolution. Working in concert with producers of all sizes, this can and should be done.

Newly named Consorzio President, Giovanni Manetti of Fontodi, is keenly aware of these issues. After the recent Consorzio tasting this February in Florence, he said, “there is still much more that can and must be done and it is one of the main objectives of my term as President to continue to boost the prestige of the denomination, contributing to consolidating its value and image in the world’s oenological excellence sector.” Manetti is an excellent choice to lead the Consorzio and he appears well-equipped to deliver on this goal.