Reprinted with permission from Red Wine: The Comprehensive Guide To The 50 Essential Varieties & Styles by Kevin Zraly, Mike DeSimone & Jeff Jenssen, Sterling Epicure, 2017.

You can’t tell an Italian what to do—but that’s exactly what prompted a group of rogue Tuscan winemakers to take matters into their own hands. The “Super Tuscan” phenomenon started quite innocently, gaining momentum only gradually, taking several decades to achieve recognition and then notoriety.

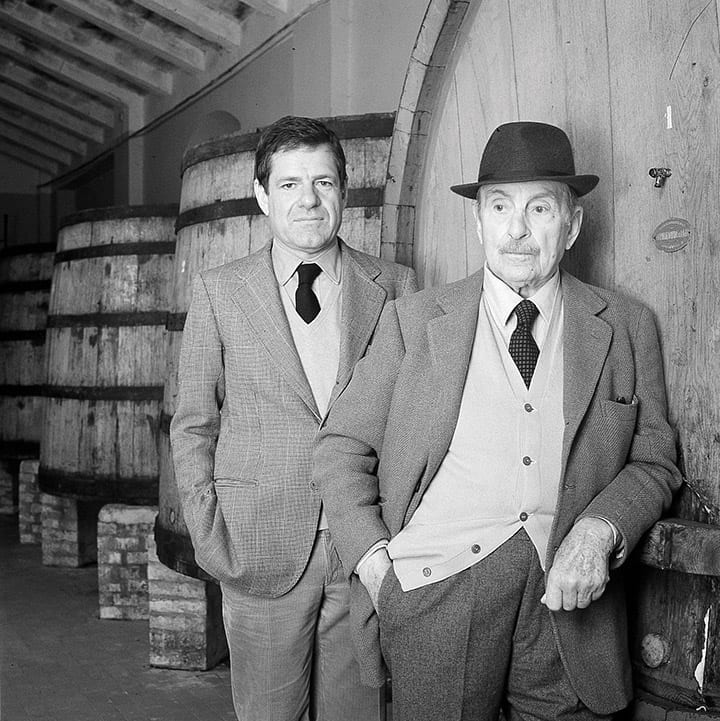

In the mid 1940s, Marchese Mario Incisa della Rocchetta and his wife moved to a horse ranch in the town of Bolgheri on the Tuscan coast. He imported Cabernet Sauvignon vines from Bordeaux and planted his beloved Tenuta San Guido estate to make wine only for personal consumption. He aged his wine in small French oak barrels rather than the large wooden casks used in the rest of Tuscany.

A few years later, a relative, Piero Antinori of the Chianti winemaking dynasty, persuaded the marchese to sell 250 cases of his wine commercially. Its individuality and quality made it an international hit. Around the same time, the Antinori family decided to buck convention and eliminate the required white grapes from their Chianti blend. (Chianti laws allowed winemakers to use up to 30 percent Malvasia, a white grape, to soften the Sangiovese.) The Antinoris added 10 percent Cabernet Sauvignon and 5 percent Cabernet Franc to 85 percent Sangiovese, more or less establishing the now-classic Tignanello blend. But tempers flared.

Because of supply and demand, winemakers conforming to Chianti DOC regulations had to sell their wines for very low prices (some less than $10 per bottle) while unregulated but highly sought wines cost more than $100 per bottle on the open market. The conformists found this irritating—to put it mildly—so the Chianti DOC punished the rule-breakers, forcing their wines to bear the shameful name of vino da tavola, or table wine. This move made the nonconformists, dissatisfied with prevailing regulations, hot under the collar, so they marshaled their ingenuity and created the indicazion geografica tipica (IGT) designation. This step helped set these new Chianti-style wines apart, but the key marketing development and the magic stroke of luck came with the all-important nickname, “Super Tuscan.” The catch-all term can apply to a wine produced with aging in mind but made from either a single varietal or a blend.

A Super Tuscan doesn’t have to be a blend, but most are, which is why it falls here in the Styles & Blends part of the book. Winemakers began using international varieties, eventually dropping the white grapes. Some even dropped Sangiovese from the blend. That’s right, a Super Tuscan doesn’t have to contain any Sangiovese! Some amazing Super Tuscans consist solely of Merlot—Tenuta dell’Ornellaia Toscana Masseto, for example. Some examples contain a blend of Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, and Syrah, while others consist of different percentages of completely different varieties.

Since the turbulent late 1960s and 1970s, Bolgheri, where all the agitation began, has restructured its percentages and aging requirements. A DOC Bolgheri wine can contain from no to all Cabernet Sauvignon, from no to all Merlot, from no to all Cabernet Franc, from no to half Syrah, from no to half Sangiovese, and less than 30 percent of “complementary” grapes defined by DOC Bolgheri’s official website as “Petit Verdot, etc.” To ensure quality, grape yield must fall below 9 tons per 2.5 acres, and the wine can’t release until September 1 of the year following harvest. A DOC Bolgheri Superiore wine must meet all the same percentage requirements, but the maximum yield is more stringent (8 tons per 2.5 acres) and the wine must age at least two years, calculated from January 1 of the year following harvest, with at least one year in oak barrels.

In The Glass: Super Tuscans can come from one or many grapes, so it’s hard to give them a specific tasting profile. They all have a complex tannic structure to allow for lengthy aging, though, which makes them all quite powerful.

Food Pairings: Because these wines have high tannins and intense power, choose bold foods that will complement their robustness. Thick steaks on the grill always work, as do spicy tomato-sauced pastas and strong cheese.

You Should Know: When the Super Tuscan style first hit the market, many of the wines retailed for more than $100 per bottle. Many of the better-known wineries retained these prices, and you can find quite a few good bottles for less than $50. If you can wait, age them for a few years. If you can’t wait and don’t dislike the fruit-bomb style, decant the wine for a few hours before drinking.

In His Own Words: “It is interesting to discover wines that challenge the rules of their regions and create something new. The choice by wine producers to focus on something so innovative shows a lot of courage. It is equally interesting to see how the choice of different grapes in the blend is dictated by their potential to perform in the terroir.”

—Nicolò Incisa della Rocchetta, owner, Tenuta San Guido / Sassicaia