In and around the quiet village of Montalcino, there is a subtle undercurrent of discussion in trattorie, bars and enoteche. You often hear it whispered in hushed tones and quieted sentiments of “you didn’t hear it from me,” but it’s hanging around like the 800-pound cinghiale in the room. There is a rising discourse to divide the Brunello zone into several separate sub-zones, and depending upon who you speak to, this would be the best thing in the last 30 years for Brunello—or an unmitigated disaster in waiting. In short, producers are divided over division.

I have visited Montalcino countless times in the past and have had many opportunities to raise the issue with winemakers. But let’s step back for a moment. What exactly is the issue? Why are we even talking about sub-zoning, or “sub-zonazione” as the Italians refer to it?

The following sections include various comments from numerous winemakers. Due to the delicate nature of the discussion, I have not included their identities.

The Background: Sub-zoning for Style along the North-South Divide

The Brunello Zone extends over 24,000 hectares, of which a mere 2,100 are under vine. As a reference, 24,000 hectares is about 100 square miles, or just slightly larger than three times the size of the island of Manhattan.

The highest elevation in the zone is principally centered around the village of Montalcino itself. The wines produced closer to this area are naturally stylistically different from those produced in other parts of the zone.

Many producers argue that this is the first reason to promote sub-zoning. Further, it’s argued that it would help consumers understand the subtle differences between the many wine styles and allow delineated subzones to become associated with certain styles of Brunello. In this fashion, the consumer would know what to expect when selecting a wine.

But as an educated writer and consumer, I’m not convinced.

One winemaker told me of a completely different, non-consumer-related reason to support sub-zoning. His family winery is a small estate with only a few acres of vineyards. Direct-to-consumer, so called “Cellar Door” sales, are crucial to his survival. Any sub-zoning project would also come with a detailed, government-funded, Consorzio-sponsored mapping of the entire zone. “With wineries accurately identified on a map, consumers will be better able to locate small wineries. The area is vast and confusing, even the locals get lost.”

These may be the obvious reasons to sub-zone or they may be the hidden red herrings. Like many debates, there is also an undercurrent of politics that permeates the discussion. There’s a North-South divide that is somehow manifested in a debate over styles. Many of the original Brunello producers are located very close to the center of Montalcino. They have a sense of pride, of purpose, that the Brunello they create is the original. That their wines are “true” Brunello. But is that accurate and will it really assist consumers? Let’s look at Brunello’s northerly sibling, the Chianti zone, for an analogy about the veracity of the supposition.

The Precursor: But…Chianti Classico does it!

The Chianti DOCG is a large parcel of land that encompasses six separate sub-zones. In essence, it’s what Brunello is using as a general model. Within the center of Chianti is the delimited “Classico” zone. Over the years, the “Classico” designation has been important for the brand and for the wines bearing the zone’s name. It’s a geographic area that has been denoted as an exceptional place to produce Chianti because the soil, climate, and exposition of the vineyards are thought to be ideal. In short, perfect terroir.

If that were the end of the equation, then such a designation would be very meaningful. However, when you factor in variables like human intervention (when to harvest) vineyard management (pruning, green harvesting, canopy management) winemaking styles (cement, stainless steel, French barrique, large casks, new oak, used oak) and not least of which, the grapes in the blend (100% Sangiovese or blends including Canaiolo, Malvasia Nera, Colorino, or even Merlot and Cabernet), then what does “Classico” mean? The average consumer will typically have no idea about any of this because none of it is required to be disclosed on labels. It’s simply a matter of knowledge. Wine geeks know. The average consumer doesn’t. Does the average consumer differentiate the Chianti Classico wines among the six other subzones of Chianti? Ask around in your local wine shop and you’ll quickly see.

The Proposal: Brunello “Classico”

But let’s get back to Brunello. With the exception of the blending issue, Brunello by law must be 100% Sangiovese, all the other variables that exist for Chianti will exist in sub-zoning Brunello. And dirt is just the start! Recently, a group of independent producers mapped the various soil types that exist in Brunello and they’ve come up with eight distinct but broad categories – many of which are combinations of each other. Now factor in altitudes, varying clones of Sangiovese, and the way they behave and grow in different soils, and you’ve just scratched the surface.

It has been suggested that the creation of a “Brunello Classico” area—wines coming from the center of the zone near the town of Montalcino—might be the first step in a broader sub-zoning project. One look at the Chianti Classico analogy should be enough to convince them of the folly in that. (Read my other article, Debunking Gran Selezione, for a glimpse at those complexities.)

What Do Brunello Producers Say?

The more I spoke to winemakers, the more I heard about highlighting the differences of the terroir. It’s a valid point. I sat down over a glass of Brunello with one such venerable producer.

Q. I first asked him straight away, is your estate in favor of sub-dividing the zone?

A. “Yes, very much in favor of starting the work on this long overdue subject of recognizing the great many differences between the vineyards of Montalcino. The facts speak for themselves,” he told me. “The height over sea level of the Montalcino vineyards goes from 300 feet to over 1,800 feet. The soil conditions vary from sandy former seabeds rich in fossils to heavy clay. The climatic conditions go from dry Mediterranean, very much influenced by coastal winds, to Continental with morning fog. As an example, you can take the official Consorzio data at harvest from October 1, 2015. In the Canalicchio Zone, Sangiovese was still below 12.5% alcohol—still a couple of weeks from picking—while in Tavernelle, the alcohol was at 14% and quite ready for harvest.”

Q. So then, what is the most important reason for sub-zoning? Is it quality, clarity of message or something else all-together?

A. “It’s mostly recognizing the reality and bringing all the producers together behind a common product; informing consumers as to the great diversity that can be found in Montalcino. And when I say recognizing the reality, I also refer to the rule in the disciplinare [regulations] of Brunello that allows producers to name their Brunello after the vineyard where it is produced. The ‘Vigna’ denomination recognizes single vineyards and is really a starting point of zoning.”

Q. So what’s the problem then? What’s standing in the way of making this happen? Is there resistance from wineries that fear that as a result of sub-zoning, they’ll be looked upon as a “lesser” Brunello if they’re in a “lesser” zone?

A. “Giovanni, I think it’s ignorance mostly, along with prejudice and politics. Concerning lesser zones, it is common knowledge in Montalcino that the heavier soils of the northeast are considered more difficult from an agronomic point of view. Well, that is the area where Casanova di Neri is located and his wine had the highest-ever rating for a Brunello. There is no lesser zone in Montalcino.”

Many other producers agreed with that sentiment. They recognize the issue is important and needs to be resolved. However, this gentleman stopped short of a full-throated desire to see sub-zoning become reality. “We are members of the Consorzio del Brunello di Montalcino, and the Consorzio is to start a study comparing composition of different soils to different altitudes, longitudes, and latitudes in order to map the whole area of the hill of Montalcino. A study that in our opinion will give a definitive view of sub-zoning.”

Not everyone necessarily agrees. Many winemakers view the issue as very complex and wondered if it could be resolved in a manner that would assist or confuse the consumer. “Montalcino terroir is so diverse that almost every producer could make realistic claims to be in a separate subzone. The possible micro-terroirs that have been outlined still lump together some very different areas and don’t fully consider the effects of altitude. And then there are the producers like us and many others who blend wine from different subzones. So really the situation is more complex than it would seem at first. In the end, I am not sure that subzones on labels would be ultimately helpful for consumers or producers.”

A Blended Terroir

The issue of producers who own vineyards scattered throughout the zone cannot be underestimated when they ultimately blend all of their fruit to produce one wine. In fact, many producers prefer to blend fruit in this manner because it gives a wine that is more representative of the overall Brunello terroir.

“For a perfect example of how sub-zoning might fall short of the desired expectations, think about the 2009 vintage in Brunello. Don’t you think that this is a year where the human decisions—canopy management, harvest timing, fruit thinning, green harvesting, etc. —totally influenced the quality of the wine? Good 2009 Brunellos are spread across all the proposed subzones. So yes, they definitely exist and we have tangible proof of terroir at every turn. However, I do believe that the market confusion would likely be enormous.”

Perhaps one of the most significant issues of all, that no one seemed to mention, is that Brunello is an international brand. Consumers the world over want a certain degree of expectation to be realized when they buy a bottle of “Brunello di Montalcino.” From China to the United States and at all points between, the Brunello brand is a significant asset that should not be risked by creating a myriad of identities that consumers will need to understand.

Unofficial Zones

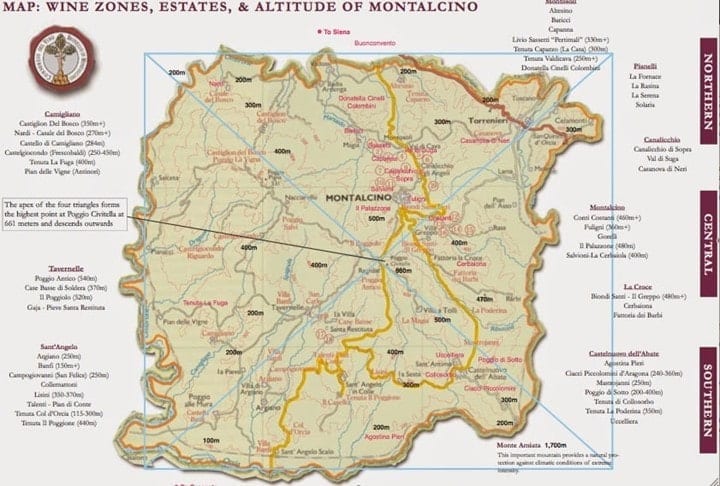

The following map, published by the Consorzio, gives a certain insight to the varying altitudes within the zone and illustrates how the zone might be bifurcated during any sub-zoning project.

On the right side of the map, the Consorzio has broadly marked “Northern,” “Central,” and “Southern” as a potential starting point for zoning. Within that framework are the loosely discussed zones that are most often mentioned: Montalcino – Bosco – Canalicchio – Tavernelle – Camigliano – Sant’Angelo – Castelnuovo dell’Abate.

It’s easy to imagine how difficult it may be for a winery to label their Brunello if they own vineyards in two or three suggested sub-zones. Which do they choose? It’s conversely very easy to imagine the trepidation a producer may feel by being forced to label their wine simply as “Brunello” when others are seemingly using more prestigious wording on their labels solely because their vineyards are located in only one zone. Is that fair? Does it matter? Ultimately, it’s up to the wineries to communicate effectively with their consumers.

Finally, the head winemaker from one of Montalcino’s largest producers told me simply:

“Even within single parts of a smaller area, the portion of a vineyard that sits at a slightly lower altitude will give wines of deeper color that are richer in tannins than wines made from grapes from higher altitudes. Furthermore, you have to realize that a large number of producers are deliberately blending Brunello wines from different zones and varying altitudes. The reason for this is obvious. In this way, they obtain more complete Brunellos than if they used grapes from a single zone only.”

So Where Does This Leave Us?

I suggest that it’s a matter that must be addressed by the Consorzio. There has to be a degree of leadership and initiative in moving the process forward; even if it comes with bruised egos and a degree of criticism from its members that is all but certain.

The data clearly supports the notion that microclimates exist all over the zone. Whether it’s from altitude, soil, exposition, or vine clone ultimately doesn’t matter. What matters most is the value of sub-zoning to Brunello. Will undertaking this complex project add a commensurate level of value to the brand that is worth the effort? Or will it hurt the brand by adding confusion and creating a sense of apathy among consumers?

Perhaps the Consorzio should answer those questions first. Instead of debating the how, when, and why to implement sub-zoning, they should be asking: Should we be doing it? I suspect the answer to that has more variations than the subzones being proposed.

Finally, one Brunello producer provided a unique perspective on the entire discussion. He told me……

“Italians typically don’t want to lead. They want to be led. In this fashion, they are free to criticize the leader.”

3 Comments

Wow! Yeah, that’s a hot mess. I agree that even many wine buyers are only attracted to perceived notions of quality and few spend the time to research deeper (my background in historical research and minor in geology helps in this regard), but to complicate it with zones that are basically Venn Diagrams as it regards grape origins, runs the risk of relegating otherwise DOCG wines to IGT. Names such as Tignanello are legendary but a relatively small producer wouldn’t necessarily benefit from the new regulations or subzoning. I think the subzones are complex and not neat little boxes of entirely like kinds, thus, it’s overly complicated for consumers and producers alike.

Agreed. Subzones may make sense to those in Montalcino but I think it would create much more complication for the rest of the world, and, specifically, for US consumers, many of whom have a hard enough time understanding the difference between Brunello and Barolo (or understanding that Chianti is a region, not a grape!). The people who are really into Brunello, do the research and understand the differences and probably don’t need another designation on the label to help them decide whether or not to buy. As with many regions around the world, much depends on the quality and style of the producer.

To clarify, I meant Tignanello as an example set apart from Chianti Classico, few Montalcino wineries would have a name to speak for itself, in my opinion.